Milestone 3 Report

Reports ·Deliver prepared datasets for use in Phase 1. Report on metrics to be used to compare the benefits of hybrid models over conventional models.

We have been working along two main work streams to continue the our development of deep learning methods for early warning signals (EWS): (1) expansion and testing of the time series EWS work presented by Bury et al. (2021)1 and (2) the development of a new spatial EWS deep learning model. Below we outline the details of the two approaches, including a deeper dive analysis of the AMOC using the time-series analysis approach. We have also summarized the datasets that we have utilized for training and testing of our models, as well as the metrics we use to assess model performance and included some preliminary results.

In general, our approach to evaluate the performance of our DL models will be to use ROC curves (receiver operating characteristic curve) to evaluate the performance of our classification model. We will compare this to the ROC curves of conventional EWS methods such as looking for increases in variance and lag-1 autocorrelation over time, in which we use a threshold value of Kendall’s tau to classify whether a time series is tipping or not.

Currently, the code for the models is available on our project’s GitHub repository. Data is currently stored locally, but we are exploring options for public data storage and this data can be made available on request.

1-dimensional time series analysis

We have continued to work with the abrupt shifts in the CMIP5 1-dimensional time series from Drijfhout et al. (2015)2. This dataset provides an opportunity to test the deep learning model from Bury et al. (2021)1. The abrupt shifts in this data are classified into 4 categories, (I) internally generated switches between two different states, (II) forced transition to switch between two different states, (III) A single abrupt change, (IV) gradual forcing to a new state. Of these categories, (III) offers the most potential for testing the DL model, however categories I and II may also represent a specific bifurcation form.

We have sorted through these 1D time series and have begun to use them to test the DL model, primarily on category III shifts, but have also considered others. Some time series have been filtered out due to the tipping point occurring very early in the time series, leaving insufficient lead up time to apply the DL model. Through this process we are looking to test whether the DL model can identify an approaching tipping point and also what type of bifurcation is commonly observed.

Table 1. Abrupt shifts identified and categorized by Drijfhout2.

| Category | Type | Region | Model and scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|

| I (switch) | 1. Sea ice bimodality | Southern Ocean | BCC-CSM1-1 (all) |

| BCC_CSM1-1-m (all) | |||

| IPSL-CM5A-LR (all) | |||

| GFDL-CM3 (all) | |||

| II (Forced transition to switch) | 2. Sea ice bimodality | Southern Ocean | GISS-E2-H (rcp45) |

| GISS-E2-R (rcp45, rcp85) | |||

| 3.abrupt change in productivity | Indian Ocean off East Africa | IPSL-CM5A-LR (rcp85) | |

| III (rapid change to new state) | 4. Winter sea ice collapse | Arctic Ocean | MPI-ESM-LR (rcp85) |

| CSIRO-MK3-6-0 (rcp85) | |||

| CNRM-CM5 (rcp85) | |||

| CCSM4 (rcp85) | |||

| HadGEM2-ES (rcp85) | |||

| 5. abrupt sea ice decrease | Regions of high-latitude oceans | CanESM2 (rcp85) | |

| CMCC-CESM (rcp85) | |||

| FGOALS-G2 (rcp85) | |||

| MRI-CGCM3 (all rcp) | |||

| 6. abrupt increase in sea ice | Region in Southern Ocean | MRI-CGCM3 (rcp45) | |

| 7. local collapse of convection | Labrador Sea, North Atlantic | GISS-E2-R (all rcp) | |

| GFDL-ESM2G (his) | |||

| CESM1-CAM (rcp85) | |||

| MIROC5 (cp26) | |||

| CSIRO-MK3-6-0 (rcp26) | |||

| 8. total collapse of convection | North Atlantic | FIO-ESM (all rcp) | |

| 9. permafrost collapse | Arctic Ocean | HadGEM2-ES (rcp85) | |

| 10. abrupt snow melt | Tibetan Plateau | GISS-E2-H (rcp45, rcp85) | |

| GISS-E2-R (rcp45, rcp85) | |||

| 11. abrupt change in vegetation | Eastern Sahel | BNU-ESM (all rcp) | |

| IV (gradual change to new state) | 12. boreal forest expansion | Arctic | HadGEM2-ES (rcp85) |

| 13. forest dieback | Amazon | HadGEM2-ES (rcp85) | |

| IPSL-CM5A-LR (rcp85) |

While this process is still ongoing, preliminary results suggest that the current iteration of the model performs well at spotting most tipping points with this form of data. There are some outliers, such as the Labrador sea convection collapse in the MIROC5 model, in which the model prediction probability of a ‘no tipping point’ scenario increases when exposed to more data. Even when this happens, the ‘no tipping point’ scenario is still less likely than a tipping point. The only exception being the Southern Ocean sea ice bimodality displayed in the BCC-CSM1-1 model, in which the likelihood of ‘no bifurcation’ exceeds that of the other outcomes prior to the tipping point.

Figure 1. Top: 1D time series of sea surface salinity showing an abrupt shift, the vertical blue dotted line shows the point prior to the tipping point, before which we analyze the time series. Below: Model output from the Bury et al DL model. The window length starts with a length of 25 and increases in length to analyze more of the time series. At each point the model predicts whether a certain class of bifurcation will occur, or whether there will be no tipping point. By the end of the time series there is a <1% chance of a tipping point not occurring, and the likeliest form of bifurcation is a fold or transcritical.

The DL model also makes a prediction of the form of bifurcation that the system may be experiencing, either Fold, Hopf or Transcritical, as seen in the example in Figure 1. For almost all of these model runs, the leading probabilities are for Fold and Transcritical, with Hopf frequently ruled out very quickly. However, there are some 1D time series that display transitions that display oscillatory properties we may expect from a Hopf bifurcation, or other higher dimensional bifurcations. Some of these time series undergo a tipping point to fluctuating behavior and then transition back into the initial state. However, the DL model does not seem to identify these as a Hopf bifurcation. More work may be required to improve the model’s ability to identify other forms of bifurcation. We have started to form an enhanced training set for this DL model by creating ‘synthetic data’ from the CMIP5 1D time series from Drijfhout et al. (2015)2. This may help to produce a model which is better able to identify other forms of bifurcation.

AMOC analysis

Following on from the previous report, where we evaluated the DL model of Bury et al. (2021)1 using time series from an AMOC collapsing in the FAMOUS GCM (Hawkins et al. 2011)3, our main focus has been the experimentation surrounding the 4-box AMOC model of Gnanadesikan et al. (2018)4 and its use in the same DL framework. The same model is also being used in the PACMANs project from the JHU/APL and we hope to collaborate with them in the coming months on this. This model is also being used by the We are using it both as a test of the Bury model, and as a training set to train a new DL model which uses the same layers as this model.

We have coded the Gnanadesikan model for use in R, with the ability to sample time series with randomly generated parameters: the vertical diffusion coefficient, the Ekman flux from the Southern Ocean, the Gent-McWilliams coefficient, the resistance parameter, and the lateral diffusion coefficient, which are sampled uniformly within the bounds tested in the original paper. Alongside this, there is the option to choose a constant freshwater flux, or one that increases over time, which would cause the AMOC to approach the tipping point. As the code chooses a start and end point for the freshwater flux over the same time period, the rate of change is different in each run. We have generated a set of 10000 time series with a constant freshwater flux, and 10000 with an increasing flux. Time series are first given 1000 years to settle to equilibrium for the initial freshwater flux value, followed by 375 years of a change in freshwater flux accompanied by a stochastic forcing to the 3 surface box temperatures (the intensity of this is also sampled from a normal distribution). Those time series that exhibit tipping (i.e. use the ‘AMOC off’ set of equations in the code), either during the equilibrium phase, or otherwise regardless of if they are in the constant or forced set are removed and replaced by another time series. This ensures that the DL is not picking up any behavior due to tipping, only the movement towards it. This also means time series can potentially get as close to tipping as possible without actually tipping.

Figure 2. Predictions from the Bury et al. 2021 DL when testing 1000 realizations of the Gnanadesikan 4-box AMOC model; 500 with a constant freshwater flux (non-forced) and 500 with increasing flux (forced). Simulations are created as described in the main text.

Taking a subsample of 500 of each and testing what the Bury model predicts, we find that for those time series not approaching tipping there is a 78.4% success rate (392 ‘no tipping’, 108 ‘transcritical’; Figure 2). However, for the 500 time series that are approaching tipping, the DL model only has a 45% success rate (10 ‘fold’, 215 ‘transcritical’, 275 ‘no tipping’). For these, we find a strong relationship between the increase in freshwater flux and the probability of the ‘no tipping’ category (Spearman’s rho = -0.346, p < 0.001; Figure 3), suggested that the Bury model finds it difficult to distinguish between those time series that have a constant flux and those where it increases only slightly (i.e. have a slow rate of change), most likely due to a strong critical slowing down signal being unobservable with only a small movement in the bifurcation parameter (freshwater flux). Furthermore the same problem of it being undecided between a fold or a transcritical bifurcation that occurred for the FAMOUS time series also appears to happen in this 4-box model too (see Milestone 2 Report).

To explore these problems, we are currently training a DL model using the same layers as the Bury model, with a binary output. The hope from this is that by being train on time series specifically related to the AMOC, it will be much clearer in its ability to detect the collapse in the FAMOUS AMOC run, and determine that the freshwater flux is constant in its equilibrium runs, something that the Bury model also struggled with. Depending on the results from this, we may explore the possibility of different types of bifurcations within the 4-box model to train a model on.

Figure 3. The change in freshwater flux (an indication of forcing) plotted against the probability of the system not approaching a tipping point according to the Bury DL model, for those 500 time series that are forced (Fig. 2). A negative correlation between these (rho = -0.346) suggests that the greater the change in freshwater flux, the less probability the DL assigns to there being no approach to tipping.

2-dimensional spatial phase analysis

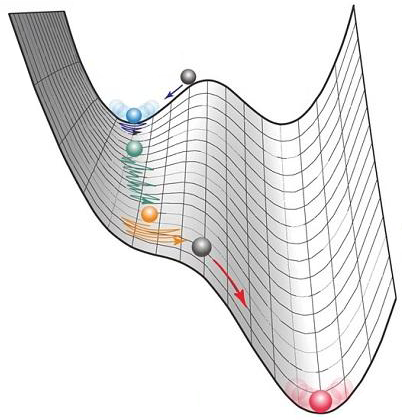

The models we have developed for early warning signal detection of phase transition tipping points in spatiotemporal systems follow a similar approach to the 1D case described above: a CNN-LSTM neural network is trained on a time series classification task, distinguishing between systems approaching a critical transition and analogous systems held far away from criticality. Instead of training on scalar measurements of a dynamical variable, however, these models aim to make use of spatial features (such as increased correlation length) which are predicted to accompany critical phenomena in many phase transitions. A theoretical analysis of early warning indicators in phase transitions presented by Hagstrom and Levin (2021)5 supports the viability of this approach, suggesting that the robustness of these models might be improved considerably by making use of the high-dimensional complexity of most systems of real-world interest.

Description of data

The models used to produce phase transitions for the training and test datasets are described in the table below. Our goal thus far has been to establish a proof-of-concept for the detection of generalizable critical phenomena. To this end, we have restricted our training set to instantiations of the simple and canonical Ising model undergoing first- and second-order phase transitions. Trained only on this data, the classifier can be tested out-of-sample on other phase transition models to determine whether it has successfully learned to identify generic critical phenomena (as opposed to any indicators that might be unique to the Ising systems).

Moving forward, we plan to introduce data drawn from a greater variety of phase transition models. By testing different combinations of which models are included or withheld from training, we hope to develop a more complete understanding of how much diversity is required in training to maximize robustness and how consistently we can expect the model to successfully generalize to out-of-sample systems.

Table 2. Spatial tipping points

| Model Name | Model Description | Train | Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Square Ising Model (1st Order) | A two-dimensional square lattice (128x128) of Ising spins interacting ferromagnetically with their nearest neighbors (subject to periodic boundary conditions). We have used the Ising model to generate training data because it is a highly canonical example of both first- and second-order phase transitions. The former are produced by smoothly varying the external magnetic field, resulting in a global turnover in system magnetization. The latter are produced by varying system temperature, leading to a transition between an ordered (low temperature) phase and a disordered (high temperature) phase. In both cases, data is coarse-grained in space and time such that the states of the lattice sites form a smooth distribution (instead of the discrete +1/-1 of the base model). | ✔ | |

| 2D Square Ising Model (2nd Order) | ✔ | ||

| Coupled vegetation-water model | This model, based on one presented in Kefi et. al. (2014), simulates a two dimensional spatial grid of variables representing vegetation biomass density and water content. Local positive feedback in the dynamics leads to a critical transition as a rainfall parameter is varied smoothly: below a threshold value, the system undergoes an abrupt desertification event. | ✔ | |

| Sea ice percolation model | This is a toy model we have developed to heuristically represent percolation phenomena in sea ice models. Percolation models are well known to exhibit static phase transitions in which saturation of a porous medium changes abruptly when site connection probability exceeds a threshold value. Golden et. al. (1998) established the importance of such transitions in sea ice modeling, where dynamics are strongly mediated by the transport of liquid brine through a frozen medium. For the purposes of this study we have developed a model which converts this static phase transition into a dynamical one: the porous lattice has site connections which melt and refreeze (open and close) with some probability, and the liquid brine percolates through this medium with simple diffusion dynamics. By varying the relative probabilities of melting and refreezing (analogous to tuning the ambient temperature), the system can be actuated through its critical threshold. This a three-dimensional lattice model, but results are averaged along the vertical axis to conform to the 2D format of the CNN-LSTM. | ✔ |

Generation of data

Training and test datasets are generated by simulation of the above models with randomized initial conditions and model parameters. In order to reduce the input dimensionality for the neural network to avoid overparameterization, we preprocess all data by computing a set of secondary statistics which are theoretically established to carry information relevant to early warning signals of critical transitions. Specifically, we compute separate spatial and temporal versions of variance, skewness, kurtosis, and 1-, 2-, and 3-autocorrelation. Temporal indicators are calculated on a rolling time window, while spatial indicators are calculated separately for each observed snapshot of the system. This results in a 12-dimensional time series, each coordinate of which is then normalized to zero mean and unit variance, as is typical for deep learning using gradient descent.

Evaluation of model performance

The principal goal of this study thus far has been to demonstrate the ability of a neural classifier to learn generic early-warning indicators for spatiotemporal phase transitions which can be used to successfully predict oncoming transitions in systems which do not appear in the training data. We have trained our classifier on Ising model simulations and tested it on the two simple environmental phase transition models described above. Results, presented in the figures below, suggest that the 2D DL model has successfully learned generalizable features from the Ising data. Models trained on both first- and second-order Ising transitions achieve classification accuracies well above baseline, with the first-order model outperforming in most tests (Figures 4 and 5). The two test models exhibit abrupt shifts consistent with the discontinuity of equilibrium associated with a first-order phase transition, so this disparity is not unexpected. That both models perform well supports the conclusions of Hagstrom & Levin (2021)5 that early-warning indicators for first-order transitions, mediated by spinodal transitions between metastable states, ought to be similar to (if not indistinguishable from) those for second-order transitions.

Figure 4. ROC curve for the CNN-LSTM model trained on first-order Ising phase transitions and tested on out-of-sample data from the vegetation-water model and the sea ice percolation model.

Results in Figures 4 and 5 are presented for neural models trained on the full set of 12 statistical indicators as well as ones trained only on the 6 temporal or 6 spatial statistics. This allows us to infer the relative contributions of each domain to the overall performance of the model. The consistently excellent performance of models which only make use of spatial information demonstrates the promise of our novel spatiotemporal approach: while further development of these methods will be necessary to see them reach their full potential, there is clearly a wealth of information available in spatiotemporal measurements which previous work on scalar time series has not been able to fully exploit.

Figure 5. ROC curve for the CNN-LSTM model trained on second-order Ising phase transitions and tested on out-of-sample data from the vegetation-water model and the sea ice percolation model.

Looking forward

In addition to the databases already described, we will start to include data collated following Bathiany, Hidding and Scheffer (2020) who use an abrupt shift detection method for CMIP5 2D variables to identify numerous abrupt shifts occurring in over half of the CMIP5 simulations. This data can be used to enhance our existing testing dataset both for our 1D and 2D DL models, and may be useful for the construction of training sets. Testing 1D and 2D DL models with this dataset will allow us to compare whether the additional information used to train the 2D DL model enhances its ability to detect tipping points.

We will also compare the performance of the 1D and 2D DL models. We will start by doing this for idealized models by extracting both a 1D time series and a spatially explicit dataset from models where they go past a tipping point - e.g. for the Kefi model, the sea-ice percolation model, or the Ising model itself. We can then compare the performance of 1D DL on the 1D output with the performance of 2D DL on the same instances. We will then move on to testing this in CMIP5 model output using the spatial data of abrupt shifts from CMIP5 as collated by Bathiany. Where the an abrupt shift (i.e. same climate model, same location in space and time) has both 1-D and 2-D output available, we will compare the performance of the 1D DL model with that of the 2D DL model, to see if the extra spatial information gives better early warning/detection, and in which cases.

We also plan targeted activity on abrupt shifts in vegetation. We will obtain additional data on such abrupt shifts from CMIP6 runs (LPJmL model run offline, or fully coupled model runs showing abrupt Amazon dieback) from collaborators. Preliminary tests show that the 2D DL perform well on Kefi’s vegetation mode. To test whether it can also perform well on more complex cases we will follow an approach similar to what we described above. Where possible we will obtain both 1D series and the spatial data from neighboring grid points to test and compare the 1D and 2D DL performance.

Finally, we plan to expand our analysis of real satellite data following the success of our analysis of the Amazon presented in a recent publication in Nature Climate Change. To begin with we will use the 1D DL model to predict if the Amazon rainforest is approaching a bifurcation, by using Vegetation Optical Depth data. If this shows promising results, we will begin to use the 2D DL model, combining results from these DL models with suggestions from the ‘manual’ indicators to give a more global view on the resilience changes of the Amazon.

-

Bury, T. M., Sujith, R. I., Pavithran, I., Scheffer, M., Lenton, T. M., Anand, M., & Bauch, C. T. (2021). Deep learning for early warning signals of tipping points. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(39). ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Drijfhout, S., Bathiany, S., Beaulieu, C., Brovkin, V., Claussen, M., Huntingford, C., Scheffer, M., Sgubin, G. and Swingedouw, D., (2015). Catalogue of abrupt shifts in Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change climate models. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(43), pp.E5777-E5786. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Hawkins, E., Smith, R. S., Allison, L. C., Gregory, J. M., Woollings, T. J., Pohlmann, H., & De Cuevas, B. (2011). Bistability of the Atlantic overturning circulation in a global climate model and links to ocean freshwater transport. Geophysical Research Letters, 38(10). ↩

-

Gnanadesikan, A., Kelson, R. and Sten, M., (2018). Flux correction and overturning stability: Insights from a dynamical box model. Journal of Climate, 31(22), pp.9335-9350. ↩

-

Hagstrom, G., & Levin, S. I. (2021). Phase transitions and the theory of early warning indicators for critical transitions. Global Systemic Risk, 1-16. ↩ ↩2