Milestone 4 Report

Reports ·Report on ‘beta version’ of hybrid model analysis including new mathematical insights, along with insights in data analysis.

In Milestone 3 we presented a summary of the datasets that we collated for training and testing our deep learning models, as well as some initial assessment of model performance. Here, we do a more in depth exploration of model performance, testing out of sample on data generated from known models. We compare the performance of our DL algorithms (both the 1D and 2D models) to conventional manual early warning signal (EWS) methods, such as lag-1 autocorrelation and variance. By doing this comparison we establish an understanding of the predictive skill of our DLs.

1-dimensional time series analysis

Model performance

In the report for Milestone 3 we presented preliminary results on the performance of our 1-dimensional DL models. Below is a summary of the model performance for various tipping points from CMIP5 models, as well as a summary of the AMOC case study.

The Bury DL model provides a probability of 4 categories - fold, hopf, transcritical or no bifurcation. The total probability of a tipping point occurring is taken as the sum of the probability of each of these categories. For the model to correctly predict an approaching tipping point, we would expect a probability greater than 50%, with a probability below this suggesting a possible false negative.

The dataset of abrupt transitions in CMIP5 models identified in Drijfhout et al.1 provides a useful resource for analyzing the effectiveness of the Bury DL model. As discussed in Milestone Report 3, this dataset contains abrupt transitions which are separated into four categories, with category III (‘rapid change to a new state’) identified as the most promising for testing these methods.

The results of this analysis are shown in Figure 1. For all of the time series considered, the DL model predicts a tipping point in each of these with a probability greater than 50%. 27 out of 31 (90%) display a probability greater than 75%, and 20 out of 31 (65%) show a likelihood of tipping which is greater than 90%. Therefore, this model seems to do well with predicting tipping points with CMIP5 data where we know of an approaching transition. There are some cases where the probability is only just above 50% which may require further investigation.

Figure 1. Histogram of the probability of an approaching tipping point for the 31 time series analyzed as part of this study.

Figure 2. Predictions from the Bury et al. 2021 DL when testing 1000 realizations of the Gnanadesikan 4-box AMOC model; 500 with a constant freshwater flux (non-forced) and 500 with increasing flux (forced). Simulations are created as described in the main text.

For the AMOC case study our main focus has been on experimentation surrounding the 4-box AMOC model of Gnanadesikan et al. (2018)2. We find that for a subsample of 500 runs that are not approaching tipping (non-forced) the Bury model predicts that there will be no tipping with a 78.4% success rate (392 ‘no tipping’, 108 ‘transcritical’; Figure 2). While for the 500 time series that are approaching tipping (forced), the DL model only has a 45% success rate (10 ‘fold’, 215 ‘transcritical’, 275 ‘no tipping’). For these, we find a strong relationship between the increase in freshwater flux and the probability of the ‘no tipping’ category.

Comparison to conventional EWS - 1D Time Series

In the following we compare the results from the deep learning (DL) model presented in Bury et al3 to conventional early warning signals (EWS) by applying these techniques to known tipping points from CMIP5. We analyzed 31 of the abrupt shifts highlighted by Drijfhout et al.1, the majority of which represent a localized collapse of convection in the Labrador sea. Other systems / tipping points included in the dataset represent a total collapse of convection, winter sea ice collapse in the Arctic and permafrost collapse.

Figure 3. A comparison of the trends in AR(1) and variance for each time series prior to a tipping point.

We see that the 1D DL model performs well at identifying tipping points in systems where we have prior knowledge that they will occur. This model clearly outperforms conventional EWS in at least 35% of our examples. However, there are two cases where the DL model identifies a tipping point with a probability just above 50% (53% and 59%), while traditional EWS show a clear indication of tipping. While this is only a small subset of the dataset, it suggests that the DL model may need further training to increase accuracy.

Comparison to conventional EWS - AMOC Model

The results on the 4-box AMOC model analysis from Milestone Report 3 (reproduced in the previous section) show that our 1d DL struggled to predict a time series approaching a tipping point when the system was only slightly forced. We now look at how generic early warning signals (AR(1) and variance changes) perform and compare this to the performance of the 1D DL. Here we use a window length equal to half the length of the time series to measure AR(1) and variance on the same subset of 500 time series from both the null and forced datasets, using values of Kendall’s tau correlation coefficient (used as a measure of tendency that is 1 if the time series is always increasing and -1 if always decreasing) as a threshold to determine if a time series is approaching a tipping point.

Figure 4. Performance of generic early warning signals when applied to the 500 subsets of the 4-box AMOC model datasets described in previous reports. Top row: Histogram of Kendall’s tau correlation coefficient values for AR(1) (used to measure tendency as described in the main text) for the null (left) and forced (middle) time series. Alongside this are the tau values for the AR(1) time series, plotted against the change in freshwater flux in each time series. Bottom row: Same as top row but for variance rather than AR(1).

Figure 4 shows the histograms of Kendall’s tau values for the null and forced datasets, alongside the scatter plot of these tau values against the change in freshwater forcing for those time series in the forced dataset. This shows that there is a slight difference in the AR(1) tau values distribution between the two datasets (top row histograms), but the difference is much more noticeable when measuring changes in variance (bottom row). The scatter plots show positive relationships between the tau values and the change in freshwater forcing, with AR(1) showing a weaker relationship than variance (Pearson’s r=0.121 and r=0.324 respectively). These scatter plots can be compared to the figure in Report 3 (reproduced below as Figure 5) that shows the relationship between the DL probability of not tipping and the same changes in freshwater forcing.

Figure 5. The change in freshwater flux (an indication of forcing) plotted against the probability of the system not approaching a tipping point according to the Bury DL model, for those 500 time series that are forced (Fig. 2). A negative correlation between these (rho = -0.346) suggests that the greater the change in freshwater flux, the less probability the DL assigns to there being no approach to tipping.

To compare these results to the Bury DL model used previously, we create ROC curves shown in Figure 6, based on the results from Report 3. This confirms that here, variance is a better indicator than AR(1) for predicting the movement towards the tipping point (AUC=0.648 vs AUC=0.557). Note that the bimodal distributions, particularly noticeable in the null distributions (Figure 4), is an artifact of choosing a window length equal to half the time series length. Choosing a smaller window would make this more normally distributed, but would also make the higher tau values lower, and harder to achieve higher thresholds in the ROC calculation. Due to this, different window lengths yield similar ROC results.

The DL performs similarly to variance (AUC=0.645), however there is clearly room for improvement and this is most likely due to those time series that are forced slowly and far away from tipping. This is leading us to train a regression DL model on the forced time series subset, measuring how far away from tipping each time series is. Currently we are exploring the addition of layers, using the same architecture as the CNN-LSTM Bury model.

Figure 6. ROC curves using subsets of the 4-box AMOC model datasets (500 null and 500 forced).

2-dimensional spatial phase analysis

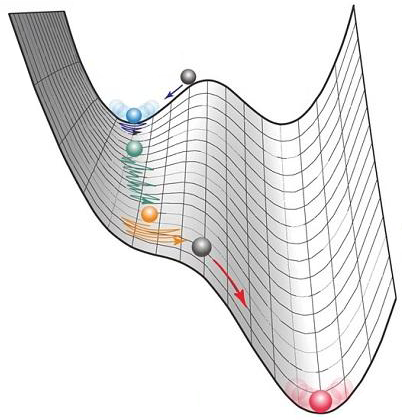

In the report for Milestone 3 we presented results for an EWS model for spatiotemporal phase transitions. A CNN-LSTM model, similar to that used in the 1D case discussed above, is trained on time series of spatial and temporal features of 2D Ising model systems undergoing phase transitions and tested on other, out-of-sample phase transition models. Two climate-relevant test models are employed: a water-vegetation system which undergoes a desertification transition as rainfall drops below a critical threshold, and a sea ice percolation model in which permeation of brine through a frozen medium increases abruptly beyond a critical level of porosity. Results, presented in Figure 7, indicate the promise of this methodology: not only do all instantiations of the model perform well above baseline (area under ROC curve = 0.5 for random classification) in spite of never being exposed to these systems during training, but the comparatively strong performance of models trained exclusively on spatial features indicates the value of accounting for spatial information which is ignored in the 1D model.

Figure 7. ROC curves for a CNN-LSTM model trained on spatiotemporal time series from second-order Ising model phase transitions and tested on two out-of-sample models of critical transitions in climate-relevant systems.

To further evaluate the efficacy of these spatiotemporal neural models, we compare their performance to that of traditional EWS methodologies. As in the 1D case discussed above, Kendall’s tau is used as a robust statistical indicator for monotonic trend in features expected to evince such a trend during the onset of a critical transition. In addition to temporal variance, skewness, kurtosis, and autocorrelation (computed on a sliding time window and then averaged across spatial coordinates), we here conduct a similar analysis on equivalent spatial features (computed separately for each temporal snapshot). Spatiotemporal phase transitions are expected to evince similar early warning signals in these spatial features, indicative of larger fluctuations away from equilibrium and longer-range spatial correlations arising in advance of the critical transition. In Figures 8 and 9, we present ROC curves evaluating the efficacy of these traditional EWS predictors as applied to our two spatiotemporal test models (12 statistical indicators were tested, but for the sake of brevity we present 3 of the best-performing ones). Although these models all rely on some mechanism of stochasticity in their underlying dynamics, the data for the simulations is unrealistically clean in that it lacks measurement noise. To understand the impact of this, we present results for classifications on time series with different levels of added white noise (with variance ranging from 0 to 1, in units of the variance of the original time series). Classifications on these noisy runs are carried out using both the traditional EWS methods and the neural models.

Figure 8. ROC curves for classification of spatiotemporal time series from a simple percolation transition model for sea ice. Results for traditional EWS methods (left) and different realizations of the CNN-LSTM model (right) are presented at varying levels of measurement noise.

We observe that while in most cases performance suffers with the addition of noise, the neural models are generally considerably more robust. Most notably, spatial variance (and temporal variance, not plotted) is a very strong predictor of transitions in clean data, but is undermined by the addition of even a small amount of noise (suggesting that it would not be a useful indicator for most real-world systems). Lag-1 autocorrelation is marginally more robust to measurement noise, but still underperforms relative to the neural models in most cases. Results for temporal skewness present something of an anomaly: though it is a very poor indicator for transitions in the vegetation system, it performs remarkably well on the sea ice model. Moreover, its accuracy markedly improves with the addition of noise. This is not entirely surprising given that we have only used symmetric additive white noise, which should not affect skewness (a measure of asymmetry) except perhaps to have some indirect regularizing effect on it. Nonetheless, it is an instructive result: not only does it underscore the capacity of different phase transitions to evince warning signals on different statistical channels, but it suggests the possibility of a wide range of possible improvements to the performance of our models using regularization methods to better isolate relevant information in messy time series.

Figure 9. ROC curves for classification of spatiotemporal time series from a water-vegetation model undergoing a desertification transition. Results for traditional EWS methods (left) and different realizations of the CNN-LSTM model (right) are presented at varying levels of measurement noise.

-

Drijfhout, S., Bathiany, S., Beaulieu, C., Brovkin, V., Claussen, M., Huntingford, C., Scheffer, M., Sgubin, G. and Swingedouw, D., (2015). Catalogue of abrupt shifts in Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change climate models. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(43), pp.E5777-E5786. ↩ ↩2

-

Gnanadesikan, A., Kelson, R. and Sten, M., (2018). Flux correction and overturning stability: Insights from a dynamical box model. Journal of Climate, 31(22), pp.9335-9350. ↩

-

Bury, T.M., Sujith, R.I., Pavithran, I., Scheffer, M., Lenton, T.M., Anand, M. and Bauch, C.T., (2021). Deep learning for early warning signals of tipping points. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(39). ↩