Milestone 5 Report

Reports ·Identify potential datasets (and providers) for Phase 2 to address predictability of climate effects at 1-to-3 decade time scales and regional or global spatial extents.

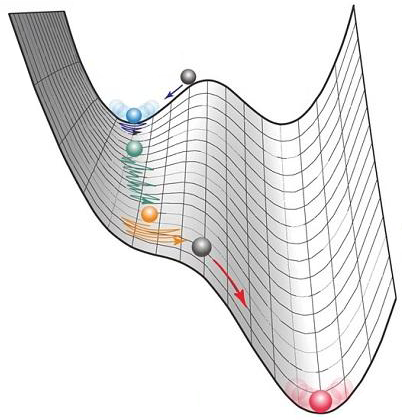

We have focused our efforts on two approaches of deep learning methods for early warning signals (EWS); a 1-dimensional time series analysis and a more sophisticated phase transition approach that also exploits information from the spatial dimensions. We have established a subset of cases with strong evidence for bifurcation and associated EWS - i.e. those with greatest potential to be accurately forecast. Below we present a selection of these potential focus systems and datasets to test our methods on for Phase 2. Some systems may only be suitable for use with our second, more sophisticated, approach as the tipping points occur across space. Finally, we filter for those cases with the potential to offer improved predictability on the timescale of interest of 10-30yr climate effects. This selection process has been based on analysis of CMIP5 model output and observational data. We have not yet analyzed output from CMIP6 models, but plan to expand our analysis of our selected focal system(s) to the CMIP6 models in Phase 2.

Ocean circulation

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is one of the most discussed tipping points. This is probably due to devastating global effects, including the interruption of the monsoon systems, and intensifying storms and decreasing temperatures in Europe, that an AMOC dysregulation would have. AMOC tipping occurs through transitions between two stable states a thermally driven regime with only a polar sinking state (TH; AMOC on), a salinity-driven regime with only an equatorial sinking state (SA; AMOC off). Our review of CMIP5 shows that one of the CMIP5 models shows a total collapse of convection in the North Atlantic (FIO-ESM under all RCP scenarios), while many of the CMIP5 models (GISS-E2-R, GFDL-ESM2G, CESM1-CAM, MIROC5, CSIRO-MK3-6-0) show a local collapse of convection in the Labrador Sea. Further, observational evidence shows that the AMOC showed “an almost total loss of stability over the previous century”. Many models in the CMIP5 ensemble (including GISS-E2-R, GFDL-ESM2G, CESM1-CAM, MIROC5, CSIRO-MK3-6-0) show a local collapse of convection in the Labrador Sea (which composes part of the North Atlantic subpolar gyre). The collapse is triggered in different RCP scenarios and on shorter timescales than the AMOC tipping.

Currently, as part of Phase 1 we are doing a focused analysis on the AMOC using both a simple 4-box model, as well as a more complex circulation model called FAMOUS. However, given the apparent higher probability of a collapse occuring in the SPG in the timescales of interest (10-30 years) we propose to shift our focus from the AMOC to the SPG tipping in Phase 2. In addition to the model data that we are currently analyzing in the context of an AMOC collapse, we would expand our analysis to observational data from previously published studies,,. Data sources that could be included in the analysis of either an AMOC or SPG collapse are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of model and observational data available for focussed analysis on AMOC and/or SPG tipping.

| Type | Name | Source | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | FIO-ESM | Link | 1.1° lon × 0.27-0.54° lat, 40 layers Monthly |

| GISS-E2-R | Link | 1.25° lon × 1° lat, 32 layers Monthly | |

| GFDL-ESM2G | Link | 1° lon × 0.375-0.5° lat, 63 layers Monthly | |

| CESM1-CAM | Link | 1.11° lon × 0.27-0.54° lat, 60 layers Monthly | |

| MIROC5 | Link | 1.4° lon × 0.5-1.4° lat, 50 layers Monthly | |

| CSIRO-MK3-6-0 | Link | 1.875° lon × 0.9375° lat, 31 layers Monthly | |

| 4-box Gnanadesikan | Link | southern high latitude box, northern high latitude box, mid- to low low latitude box, deep box continuous in time | |

| FAMOUS | Link | 3.75° lon × 2.5° lat, 20 vertical levels 1 hr time step | |

| Observational | OSNAP | Link | East and west domains 30 day |

| MOVE 16°N | Link | Daily | |

| SAMBA 34.5°S | Link | Daily | |

| HadISST reanalysis data | Link | 1°x1° Monthly |

Cryosphere

In addition to tipping points in the AMOC system, abrupt shifts in CMIP5 models often occur in the cryosphere. These include the collapse of winter sea ice in the Arctic (in the following models: MPI-ESM-LR, CSIRO-MK3-6-0, CNRM-CM5, CCSM4, HadGEM2-ES) and an abrupt decline in sea ice cover in high-latitude oceans (CanESM2, CMCC-CESM, FGOALS-G2, MRI-CGCM3). In addition to this, abrupt snow melt in the Tibetan Plateau is seen in the GISS-E2-H and GISS-E2-R models.

Elements of the cryosphere are expected to change in a warmer world. Some aspects of this system could provide a target of further research in Phase 2. The CMIP6 ensemble provides a further potential dataset to search for tipping points in the cryosphere and an opportunity to further apply our deep learning models to predict these tipping points.

Recent research with real-world data has identified critical slowing down, i.e. resilience loss associated with an approaching tipping point, in the Greenland Ice Sheet. Tracking ice sheets and glaciers with remotely sensed data may provide an avenue for detecting tipping points in these systems. While a comprehensive study to this effect may be beyond the scope of Phase 2, it is worthwhile to consider the utility of remote sensing to detect glacial retreat and tipping point.

Table 2. Summary of model and observational data available for focussed analysis on cryosphere tipping.

| Type | Name | Source | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | MPI-ESM-LR | Link | 1.5° lon × 1.5° lat Monthly (2 runs with daily data) |

| CSIRO-MK3-6-0 | Link | 1.875°lon × 0.9375° lat Monthly | |

| CNRM-CM5 | Link | 1°x1° (for ocean) 1.4°x1.4° (for atmosphere) Ice is divided into 10 vertical layers Daily and monthly | |

| CCSM4 | Link | 1.125° lon × 0.27-0.64° lat, 5 layers Monthly | |

| HadGEM2-ES | Link | 1° x 1° Daily and monthly | |

| CanESM2 | Link | 2.8125° lon x roughly 2.8125° lat Daily and monthly | |

| CMCC-CESM | Link | 2° lon × 0.5-2° lat, 3 layers Daily and monthly | |

| FGOALS-G2 | Link | 1°×1°, 5 layers Daily and monthly | |

| MRI-CGCM3 | Link | 1° lon × 0.5° lat Daily and monthly | |

| GISS-E2-H | Link | 1° lon × 0.2-1° lat Daily and monthly | |

| GISS-E2-R | Link | 1.25° lon × 1° lat Daily and monthly | |

| Observational | Sentinel-1 SAR | ESA/USGS | 5m×20m, 6-day |

| Sentinel-2 | ESA/USGS | 10m and 20m, 5-day | |

| Landsat | USGS | 30m, 16-day |

Terrestrial systems

In order to optimize water usage in dryland systems, vegetation can form distinct spatial patterns. These patterns belong to a class of reaction-diffusion systems where localized feedbacks give rise to spatial patterning, as first recognised by Alan Turing. Occurring in drylands across the world, the morphology of these patterns has been hypothesized to provide an indicator of the system’s resilience. As precipitation levels change, so does the morphology of these patterns.

Much of the study of these patterns has focused on the use of pattern vegetation models, or occasional aerial photography, although high resolution satellite data has been shown to be capable of quantifying changes in these patterns. While previous studies have shown where these patterns are likely to occur, applying machine learning pattern recognition techniques to high resolution satellite imagery (such as Sentinel-2 data) provides an avenue to comprehensively identify these patterns and to track their resilience. This may provide an indication of wider trends in vegetation resilience across drylands. These pattern detection models can be trained on vegetation models which simulate these patterns before being applied to satellite data.

Figure 1. ROC curves illustrating the accuracy of the phase transition DL model applied to abrupt transitions in CMIP5 data, separated by Earth system domain.

Preliminary results obtained from the phase transition deep learning model applied to spatiotemporal time series from abrupt shifts observed in CMIP5 data suggest strong performance on these terrestrial variables, perhaps as a result of their propensity for spatial patterning. Figure 1 presents ROC curves plotting false vs. true positive rates of model classification on CMIP5 data from three domains: Amon (Monthly Mean Atmospheric Fields and Some Surface Fields), Lmon (Monthly Mean Land Fields, Including Physical, Vegetation, Soil, and Biogeochemical Variables), and OImon (Monthly Mean Ocean Cryosphere Fields). While the model achieves above-baseline success on all domains, its performance is far superior on the terrestrial Lmon variables. Other CMIP5 domains, including LImon and Omon (land cryosphere and oceanic field variables, respectively), are omitted from this analysis because they lack sufficient representation in the catalog of observed abrupt shifts used to construct the data set. Further analysis on the performance of the phase transition deep learning in CMIP models ongoing and we aim to report on this in the next milestone report.

Table 3. Summary of model and observational data available for focussed analysis on terrestrial system tipping.

| Type | Name | Source | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Konings et al. Pattern vegetation model | Link | |

| HilleRisLambers et al. 2001 pattern vegetation model | Link | ||

| Rietkerk et al. 2002 pattern vegetation model | Link | ||

| Observational | Sentinel-2 | ESA/USGS | 10m and 20m, 5-day |

| Landsat 8 | USGS | 30m, 16-day |

This result indicates that terrestrial tipping phenomena associated with the data sources listed in Table 3 may present particularly fruitful test cases for the spatiotemporal phase transition DL classifier. Although it is not entirely surprising that the inclusion of spatial feature analysis may be less useful for atmospheric and oceanic cryosphere domains (in which diffusive mixing dynamics are more likely to suppress spatial patterning), further analysis is required to understand the potential of the phase transition model in these cases. Modifications to the training library designed to promote sensitivity to features at different time or length scales, for example, may offer improved performance (e.g. through superior detection of short-lived spatial structures), especially in observational data sets available in considerably higher spatial and temporal resolution.

Alongside detecting spatial patterns in vegetation, we also propose to detect changes in resilience in remotely sensed observation data, such as those in the table above. These data would take the form of 1D time series which would be fed into the Bury et al. DL model used in other reports. Feeding the model with more of the time series over time should provide us with information about the change in resilience in the system; an increase in the probability of tipping over time would suggest the system is losing resilience. This would provide a comparison to our previous work, such as using Vegetation Optical Depth to determine a loss of resilience in the Amazon rainforest over time.