Milestone 1 Report

Reports ·Identify constituents of the hybrid models along with planned datasets and the problems and target effects to be investigated.

The aim of the University of Exeter / University of Waterloo project is to continue development of a deep learning approach for identifying early warning signals (EWS) of tipping points in the climate system. This project will extend on work that was recently published in PNAS1, which used a CNN-LSTM (convolutional neural network—long short-term memory network) to provide EWS. The results showed how deep learning algorithms can provide EWS of tipping points in real-world systems.

The overall objective of this first task was to identify appropriate data sources to be included in an expanded training dataset and identify ways to improve the deep learning algorithm. This is accomplished following two main streams of work. In the first stream we extend our training dataset to include a wider class of bifurcations and a wider range of known model cases of them. Additionally, we have identified appropriate spatially explicit datasets in which there are bifurcations. Including these in the training will give the CNN the opportunity to learn spatial EWS. We have also identified further opportunities to augment the training dataset. In the second stream we identified opportunities to improve the network performance, such as extending the training dataset and improving the network architecture.

Early warning signals

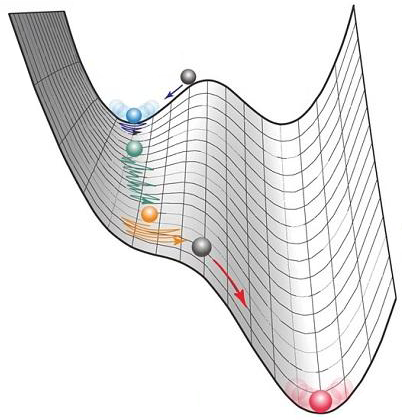

Early warning signals (EWS) are a group of statistical signals that can be used to anticipate a critical transition before it is reached. EWS are universal, model-independent indicators that have grown in popularity to support evidence of an approaching bifurcation event. Existing EWS detection methods monitor changes in e.g. variance and lag-1 autocorrelation AR(1) over time, increases of which suggest a movement towards a bifurcation. Spatial analogues of these temporal measures can also be used. The use of spatial techniques (e.g. spatial correlation) can supplement a lack of temporal data; a value of an indicator can be determined from a single time point, rather than needing a time-window to measure the statistic on.

Deep learning (DL) approaches offer 2 major advantages over these traditional EWS methods. DL allows for more sophisticated diagnostics (e.g. could learn to incorporate information from higher-order autocorrelation coefficients), as well as the ability to identify different signatures associated with different types of bifurcation.

Training data

Previous work has used an innovative approach to generate a training dataset that is generalizable to systems that the DL is not trained on. Exploiting the fact that dynamical patterns near a bifurcation point simplify - which allows us to relax the restriction that DL algorithms can only classify time series from systems that they were trained on - training datasets were generated that allowed the CNN to learn universal heuristics from synthetic data. Bury et. al. (2021)1 constructed a training dataset from simulations of randomized 2D dynamical systems that contained polynomials up to 3rd order. Bifurcations were then identified using AUTO-07P2. Similarly, Deb et. al. (2021)3 developed a novel detection method, using simulated outcomes from a range of simple mathematical models with varying nonlinearity to train a deep neural network to detect critical transitions - the Early Warning Signal Network (EWSNet).

Our current approach

Currently, we generate our training data by creating instantiations of a given bifurcation species by perturbing the normal form with randomized higher-order polynomial terms, e.g.:

x’=+x2+fx

This produces a fold bifurcation for any f(x) whose Taylor expansion about x = 0 consists of only terms of order 3 or higher. By doing this often we create a training dataset on which we can train our CNN-LSTM neural network to classify bifurcations.

Expanding to Spatial Data

EWS have traditionally been applied to temporal information, but research shows that the information provided by the additional dimensions in spatial data could also provide indications of approaching transitions. For systems that are not well mixed, changes in spatial characteristics of the system could provide EWS4. This has been shown for ecosystems, where the spatial structure of ecosystems can provide information about the ecosystem degradation level. Well-resolved spatial data is becoming increasingly available at low cost due to improved technology (such as remote sensing). Furthermore, gridded climate data, such as that from CMIP5 and CMIP6 model output, provides information stemming from the spatial component. Applying bifurcation theory assumes dominant dynamics are given by some ODE on a relatively low-dimensional manifold. This is true sometimes, but not generically — climate models utilize complex PDE models on high dimensional lattices to generate their output. There are, however, spatial indicators for impending transitions in lattice systems that are generalizable across many examples, similar to temporal EWS for ODE bifurcations. We will begin with a classic Ising model to generate a training library of spatial transitions. Variants of the classical Ising will be developed to generate a broader range of transition types (e.g. Ising model on a sphere with random parameters, sampled at various levels of coarse-graining). We will then move on to use spatial data from CMIP5/CMIP6 simulations, as well as a library of transitions in spatial models, chosen to represent a broad range of possible transitions to build a training set for spatial EWS.

Identification of additional training data sets and further improvements

We will spike the universal library of local bifurcations with examples specific to climate change, we hypothesize that the sensitivity and specificity of the algorithm will improve. In this way we will “integrate existing knowledge (atmospheric/ocean chemistry, physics, and terrestrial biology) and diverse data” into our deep learning approach.

We have developed a workflow for automatic abrupt shift detection5 which colleagues at the Potsdam for Institute of Climate Research have automated and added a clustering algorithm. The approach provides insight into spatial structures and temporal dynamics of large-scale tipping elements, resolving tipping on smaller scales, which may be otherwise overlooked (i.e. considering aggregates over large areas such as climate zones). This workflow will be used to identify tipping points in CMIP5 and CMIP6 model runs. We will then include the time series of the identified tipping points in our training dataset.

We can also take advantage of GCM experiments specifically run to examine how climate systems collapse. Examples of these include a FAMOUS run of AMOC collapse6, and runs from the HELIX project, that looked at high end climate impacts and extremes (for example in Jackson et al., 20157). The AMOC collapse run provides a 3D array over time, allowing the possibility to observe how DL methods behave using this extra information.

In summary, we have identified the following steps to augment the training set:

Combine synthetic data from our method and those of Bury et. al. and Deb et. al. into a master training set to improve diversity of examples Create hybrid data sets of synthetic and real data for abrupt transitions and train models on these (either simultaneously or sequentially). Include spatial data in training dataset Explore alternate methods for generating dynamics which exhibit universal, generalizable early warning signals in advance of abrupt transitions

Improve Network Performance

The efficacy of the trained classifier model depends on the quality of the training data set and the architecture of the neural network itself. To this end, we plan to explore a number of possible improvements to the design of the CNN-LSTM base model. In order to better accommodate a wide range of time scales in observed dynamics, we have begun implementing a module inspired by the InceptionTime network, which represents the current state of the art in neural time series classification8. This architecture replaces the simple convolution layers of our model with multiple, parallel convolutional computations of differing kernel sizes, allowing for robust multiscale feature identification.

Additionally, we have begun experimenting with networks better adapted to multivariate data. In the interest of accommodating gridded spatial data, we must consider how a much higher-dimensional (and spatially ordered) input signal can be efficiently represented in the neural network without an overwhelming number of free parameters. We have achieved some preliminary success by compressing data on an NxN grid down to a few variance- and autocorrelation-based statistical indicators (spatial and temporal) which are used in traditional approaches to early warning signal detection, and training the CNN-LSTM network on those preprocessed time series. We hope, however, to implement a solution more in the spirit of deep learning methods, wherein a preliminary pooled convolutional layer will learn a compressed representation for gridded input data which preserves salient EWS information in a much lower-dimension to be passed to the following layers of the network.

Ultimately, we hope to construct a model capable of synthesizing spatiotemporal time series associated with multiple climate variables measured simultaneously. Depending on the data source, this may require that the network be robust to data sampled at differing spatial resolutions. In this case, we may need to replace traditional convolutional modules (in which data is convolved with learned filters of fixed size) with more adaptable operator-based methods (in which a kernel function agnostic of spatial sampling intervals is learned instead9). The CMIP5 spatial test data with which we are currently working is largely sampled at uniform resolution, however, so this is not an immediate priority.

Potential collaboration

During the project kick-off meeting in December we identified some opportunities to collaborate with other research groups. These include using a low-order model of ocean circulation10 developed by Anand Gnanadesikan (Johns Hopkins University, ‘PACMANs’ project), which can be calibrated to emulate the behavior of different GCMs (e.g. CMIP6 models), as part of our training dataset. Also, we agreed to share output from the AMOC collapse simulations of Jackson et al. (2015) with the DeepONet project.

Open Questions

Below is a list of remaining questions that we will explore prior to Milestone 2 and test prior to Milestone 3:

- If a synthetic data set generated using Ising model simulations turns out to be insufficiently diverse for generalization, what properties should we look for in other phase transition models to tease out the universal early warning signs?

- How best to train models on data from multiple sources? A single large hybrid data set? Train first on one, then the other (universal → specific)?

- Linked to the question above, how much can we learn during the training of models that consider different aspects of the climate system, e.g. Amazon rainforest dieback versus AMOC collapse. The dynamics of these systems are at different timescales and as such how much learning from one system can we use for another?

- How much should we be relying on synthetic vs. real data? Is it possible that downloading more CMIP simulations and building a larger set could obviate the need for synthetic training data?

- How do we take advantage of data from the GCMs where the system in question does not tip in that simulation? For example, can we build up a ‘null model’ expectation from e.g. GCM control

-

Bury, T. M., Sujith, R. I., Pavithran, I., Scheffer, M., Lenton, T. M., Anand, M., & Bauch, C. T. (2021). Deep learning for early warning signals of tipping points. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(39). ↩ ↩2

-

Doedel, E. J., Champneys, A. R., Dercole, F., Fairgrieve, T. F., Kuznetsov, Y. A., Oldeman, B., … & Zhang, C. H. (2007). AUTO-07P: Continuation and bifurcation software for ordinary differential equations. ↩

-

Dev, S., Sidheekh, S., Clements, C. F., Krishnan, N. C., & Dutta, P. S. (2021). Machine learning methods trained on simple models can predict critical transitions in complex natural systems. bioRxiv. ↩

-

Kefi, S., Guttal, V., Brock, W. A., Carpenter, S. R., Ellison, A. M., Livina, V. N., … & Dakos, V. (2014). Early warning signals of ecological transitions: methods for spatial patterns. PloS one, 9(3), e92097. ↩

-

Boulton, C.A., & Lenton, T.M. (2019). A new method for detecting abrupt shifts in time series. F1000Research 2019, 8:746 ↩

-

Hawkins, E., Smith, R. S., Allison, L. C., Gregory, J. M., Woollings, T. J., Pohlmann, H., & De Cuevas, B. (2011). Bistability of the Atlantic overturning circulation in a global climate model and links to ocean freshwater transport. Geophysical Research Letters, 38(10). ↩

-

Jackson, L. C., Kahana, R., Graham, T., Ringer, M. A., Woollings, T., Mecking, J. V., & Wood, R. A. (2015). Global and European climate impacts of a slowdown of the AMOC in a high resolution GCM. Climate dynamics, 45(11), 3299-3316. ↩

-

Fawaz, H. I., Lucas, B., Forestier, G., Pelletier, C., Schmidt, D. F., Weber, J., … & Petitjean, F. (2020). Inceptiontime: Finding alexnet for time series classification. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 34(6), 1936-1962. ↩

-

Li, Z., Kovachki, N., Azizzadenesheli, K., Liu, B., Bhattacharya, K., Stuart, A., & Anandkumar, A. (2020). Fourier neural operator for parametric partial differential equations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.08895. ↩

-

Gnanadesikan, A., Kelson, R., & Sten, M. (2018). Flux correction and overturning stability: Insights from a dynamical box model. Journal of Climate, 31(22), 9335-9350. ↩